Confidently Misled (Part 3 in the Changing Minds Series)

Every decision rests on how we know what we know. But what happens when the ground beneath our knowing shifts without our awareness? When speed replaces wisdom, we risk losing the very capacity to recognise truth—trading discernment for productivity.

Before the Word Gets Heavy

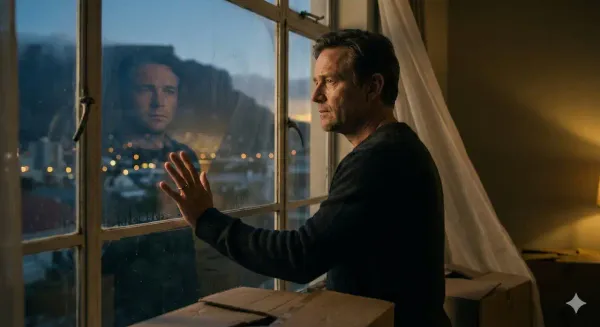

The cost is what you can no longer see.

Epistemology sounds like one of those words that belongs in a university library, not in a kitchen conversation. But all it really means is this: how we know what we know.

Every decision we make, every belief we hold, rests on some way of knowing. Sometimes it’s experience, sometimes it’s what we’ve read or been told, sometimes it’s simply what feels right.

But here’s what we began to uncover in part 1 and part 2: what we “know” is rarely solitary. It lives inside clusters—networks of beliefs, habits, and relationships that reinforce each other. Our identities form in these clusters. We belong to them, and they belong to us.

The apostle Paul named these entrenched patterns when he spoke of logismos—reasoned arguments, intellectual barriers, the fortified strongholds that set themselves up against the knowledge of God (2 Cor. 10:5). He wasn’t picturing abstract philosophy; he was using military imagery, describing the work of dismantling false reasoning as an assault on a fortress.

These strongholds are not built of stone but of story—woven through our belonging, reinforced by the voices we let speak without challenge.

Change one belief, and you tug on the web that holds it in place—friends, communities, memories, even our sense of self. No wonder facts alone rarely change minds. We are not brains on sticks; we are relational creatures whose knowing is shaped by who we are with, and who we trust.

Epistemic risk, then, is not just the danger of being wrong about a fact. It is the risk that our entire network—the way our beliefs and our belonging are intertwined—has been tilted without our awareness. That the foundations of what feels true have been shifted by forces we neither see nor chose, and that the very cluster we rely on to test truth might resist correction because it would mean unravelling too much of who (we believe) we are.

And it’s right here — when the ground under your 'knowing' shifts — that faith in who God is and what He has revealed of His nature and character and, the trustworthiness of what He has promised begins to resemble Abraham’s — standing firm when the evidence around you seems thin, when the network you’ve trusted is swaying. Paul called this being “fully persuaded” that God is able to do what He promised (Romans 4:21).

When the Ground Moves Under Your Feet

And here’s where our modern moment presses hard on these clusters of knowing. They are not just formed in the living room, the church hall, the long friendship—they are now constantly bathed in currents of influence that arrive through the phone in your pocket, the screens that surround you.

Not blunt intrusions, but subtle drips.

Adjustments to what you see first.

Nudges in what gets repeated.

Patterns in what gets rewarded.

When the ground on which your knowing stands is shaped by unseen hands, you begin to mistake familiarity for truth. A phrase feels right not because it’s been tested in the fires of lived experience or the counsel of trusted voices, but because you’ve seen it so many times it feels like your own thought.

The Temptation of the Upgrade

What came with technology was a flood of information and mobility. It looks a lot like the “Many shall run to and fro, and knowledge shall be increased.” of Daniel 12:4. Most are overwhelmed. Add fake-this and fake-that to the flood and it’s becoming harder to know what to believe. What is right, what is wrong.

This is where the allure of the tools comes in. They promise to manage the flood for you—sort it, streamline it, deliver it in digestible form. Speed, reach, capability. They say you’ll be freer if you just automate, optimise, integrate — give our personal lives to a Personal Digital Assistant. But if Parts 1 and 2 have shown us anything, it’s that the more subtle the influence, the more dangerous its hold.

And here’s the uncomfortable truth: we rarely stop to consider whether the gains are worth the trade—not in hours or profit, but in truth itself.

Epistemic Risk Check

Before adopting a new tool or process, ask:

- What sped up?

- What got automated?

- What communal friction did I lose?

If the answer to #3 is “a lot,” the tool might be taxing your capacity to know.

When the Cost Is What You Can No Longer See

Media theorist Neil Postman warned in Technopoly (1992) that every new technology “creates a new environment” and, left unexamined, “will use us as its instruments.” More recently, Shoshana Zuboff (The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, 2019) has shown how algorithmic systems are designed to shape human behaviour toward predictability—because predictability is profitable. I can personally testify to this fact as I have run multiple Google & Facebook Ads campaigns—optimising the targeting based on user profile and intent. These algorithms are very capable of finding just the people you want to put your message in front of.

The gains in productivity and reach come with a (high) cost: epistemic risk, the risk that we lose the slow, embodied, relational work by which humans learn to discern.

This manipulation isn't new—it's as old as the human heart's tendency toward deception.

The apostles would recognise this risk—not because they knew about algorithms, but because they knew the human heart.

This is why they urged believers to “let the word of Christ dwell in you richly” (Colossians 3:16), not just in private study but in psalms, hymns, spiritual songs, in the shared air of gathered life.

They knew that words, to form, must live in a body—not in isolation, as practically demonstrated by the Bereans in Acts 17:10-12, and certainly not in automation.

This is why the writer of Hebrews insisted:

"not abandoning our own meetings, as some are in the habit of doing, but encouraging each other, and all the more so because you see the day drawing near."

— Hebrews 10:25

The 'foolishness of preaching', the 'gathering of the local body', the 'whole body, joined and held together by every supporting ligament', is His wisdom — our protection — in this age of confusion and endless voices leading us into being 'double minded'. All these work together to protect us in this 'how we know' reality of the algorithmic age.

When Speed Works Against Wisdom

The problem with pursuing productivity without reflection is not simply that we might go faster in the wrong direction—it’s that we may lose the capacity to recognise direction at all.

Discernment requires friction: pauses, disagreements, the “seeing through a glass darkly” moments where truth is forged in the presence of others. Productivity culture teaches us to sand down those rough edges because they slow the output. But in doing so, we strip away the very conditions in which our knowing becomes trustworthy.

The Risk You Carry Without Knowing

Epistemic risk is not a philosopher’s luxury — it’s the danger you carry into every thought, conversation, decision, and prayer. It is the possibility that your sense of what is true has been quietly warped by repetition, reward, and reinforcement loops that feel like your own thinking.

I’ve found myself defending a position I later realised had nothing to do with conviction or biblical persuasion — and everything to do with the network, the echo chamber I was immersed within.

I can still feel the tightening of my neck and shoulder muscles from that conversation — the way I doubled down, not because I was right, but because backing down felt like betraying my people.

The tilt wasn’t malicious; it was ambient. And yet it shaped me.

The Apostolic Countermeasure

Paul’s counsel to the Thessalonians was deceptively simple: “Test everything; hold fast what is good” (1 Thess. 5:21). But testing requires a standard—and that standard must be more stable than the feed, more enduring than the trend cycle, more human than the metric.

This is why the apostles tied knowing to dwelling—as in the knowledge of Christ.

Not to consume, but to abide.

Not to skim, but to inhabit.

And always together, because truth-in-isolation hardens into self-confirmation, while truth-in-community humbles, corrects, and slowly reshapes the very network of belonging that makes something feel true.

Standing at the Edge of the Noise

So the question before us is not, How much more can we do with these tools? It is, What do these tools do to our capacity to know?

Because if the cost of productivity gain is the erosion of discernment, then the bargain is worse than false—it’s a slow apprenticeship into blindness.

In the next step of this journey, we will step into the noise itself. The swirl of voices, notifications, and opinions that fill our waking hours. And we will ask: When the voices compete for my trust, how do I know which one is the Shepherd’s?