The Invisible Hand on the Scale (Part 2 in the Changing Minds Series)

When your choices feel free, a quiet weight may still tip the scale. Algorithms, old loyalties and tiny nudges shape what you trust. What if the scale you rely on was never level? Read on to learn how to spot the tilt—and reclaim the balance that makes belief real. Notice the hands that tilt truth!!

“Your ‘free choice’ is being weighed for you.”

If the crack in our certainty opens the door, what waits beyond it is not a clear view — but a room where the furniture has already been quietly rearranged.

It begins so subtly you almost miss it. Not a shove, not a command — just the quiet weight of a finger resting on the scale. A change so slight it feels like you’re still choosing freely. But the outcome… it keeps leaning one way.

You like to think you see clearly. That if the facts were different, your conclusions would be too. Yet something — unseen, unmeasured — keeps tilting your balance.

Invisible Bias, Visible Effects

Sometimes the scale is tilted by design. An algorithm trained on what held your gaze yesterday, feeding you more of the same today. Sometimes it’s older than code — the echo of a voice you once trusted, an authority who framed the world for you in a certain way, so now every new thing you learn sits inside that frame.

Facts enter — but the identity you’ve built decides whether they live or die. And identity does not yield to data. It bends data to itself.

Learning to Build Habits – and Break Them

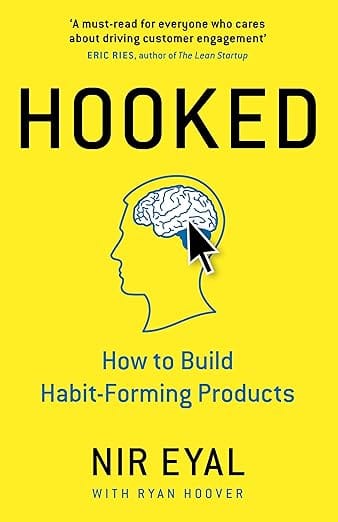

This isn’t abstract for me. Years ago, as part of my marketing work, I studied Hooked by Nir Eyal.

It was a sharp, practical guide to building habit-forming products—built around his “Hook Model”: trigger, action, variable reward, investment. The brilliance—and the danger—was in how it married behavioural psychology with product design.

It was no secret that Silicon Valley companies took this playbook and embedded it deep into the software billions use daily, from social media feeds to productivity apps.

Eyal himself acknowledged that companies like Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn adopted such strategies to make their platforms “habit-forming” in the neurological sense (Eyal, 2014). The results were devastatingly effective: human attention captured, behaviour shaped, without the user’s full awareness.

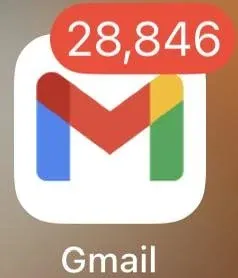

The Tyranny of the Little Red Dot

One of the clearest examples Eyal pointed to was what he called “the tyranny of the little red dot.”

A simple notification badge—a tiny red circle with a number—acts as a visual trigger that our brains find almost impossible to ignore. It signals something new, potentially rewarding, and taps into what psychologists call the “variable reward” loop. You don’t know what’s waiting until you tap, so you tap—again and again.

It’s a small, seemingly harmless design choice, yet it exploits deep neurological pathways, training the user to seek that intermittent reward without conscious thought. This is not accidental; it is engineered attention capture, woven into the fabric of modern interfaces.

Becoming Indistractable

Years later, Eyal released Indistractable—a personal and cultural counterpoint to Hooked. In its pages, he tells how his own family and children became caught in the very attention traps his earlier framework had helped optimise.

The book’s central premise is that to be “in-distract-able” is not merely to resist temptation, but to build a life in which our actions align with our deeper values, rather than with the manipulations of our tools (Eyal, 2019). It is a call to reclaim agency over what and who forms us.

That word—in-distract-able—has a scriptural echo. Paul urged the Corinthians to “be steadfast, immovable, always abounding in the work of the Lord” (1 Corinthians 15:58). The writer to the Hebrews warned, “We must pay much closer attention to what we have heard, lest we drift away from it” (Hebrews 2:1). In both cases, the idea is the same: anchoring one’s attention and devotion in the truth of Christ so that the currents of the age do not carry us off-course.

If Eyal’s later work was about regaining focus in the face of digital distraction, the apostolic witness goes further—it is about reorienting that focus toward the living Word, within the body, in shared obedience.

What the Algorithm Cannot See

There is a strangeness to our age: the most precise systems in history are blind to what matters most. They can count the seconds you hovered over a video but cannot see the knot in your chest as you watch it. They know the headlines you click, but not the story you tell yourself after reading them.

And this blindness is not neutral. Because the unseen is not un-felt. Your deepest responses remain hidden, even from you at times — but they steer you all the same.

A Personal Tilt

I’ve felt that tilt in my own hands.

I had a business years ago where every decision I made felt “mine” — until I realised I’d been quietly funnelling all my thinking through the preferences of a partner I wanted to please. Not because they demanded it, but because I needed them to see me as competent. Approval was the invisible hand that tilted my scale.

Once I saw it, I couldn’t unsee it. And it unnerved me — how much of what I thought was “objective” was actually bent by desire, by belonging, by fear of losing either?

The Emotional Cost

When the scale is off, it’s not just accuracy that suffers — it’s trust. You begin to doubt your own reasoning, wondering if you’ve ever truly chosen freely. And when trust erodes, some withdraw completely. Others double down, defending the tilt as if it were level ground. Some feel the ache but have no language for it, so they carry it in silence.

Each response comes from somewhere real — a past shaping, a wound, a loyalty, an offence, a hope that refuses to die.

The Apostolic Mirror

Paul spoke to this in his second letter to the Corinthians. He described minds “blinded,” not by ignorance alone, but by a veil only Christ could remove (2 Cor 3:14–16). The removal of the veil is not an intellectual achievement — it’s a relational unveiling.

Truth comes not to the proud collector of data, but to the one willing to stand, unveiled, before the Lord.

And that unveiling is costly, because it may expose that the scale you trusted was never true. And trust is key.

Paul cites Abraham’s trust in God as not naive — he believed against hope, fully aware that his age and Sarah’s barrenness made the promise humanly impossible. Faith acknowledges facts; it does not ignore them.

(ESV) 18 In hope he believed against hope, that he should become the father of many nations, as he had been told, “So shall your offspring be.” 19 He did not weaken in faith when he considered his own body, which was as good as dead (since he was about a hundred years old), or when he considered the barrenness of Sarah’s womb. 20 No unbelief made him waver concerning the promise of God, but he grew strong in his faith as he gave glory to God, 21 fully convinced that God was able to do what he had promised.- Romans 4:18–21

Paul carried that same grit into his calling, knowing the pull of the world’s scales. Seeing the tilt is not cause for despair, but a summons to anchor in the One who does not shift.

Why This Matters

If unseen hands are on our scales, then the question is not simply “Do I have the right facts?” but “Who — or what — is weighing them for me?” Left unexamined, this is how we stay trapped in echo chambers, convinced we’re reasoning while we’re only rehearsing.

The way forward is not frantic fact-checking, nor cynical withdrawal, but a willingness to notice — and name — the subtle forces shaping what we call truth. Only then can the balance be restored.

The 48-Hour Tilt Log

For the next two days, note three moments when something shifted your view without you planning it.

- The dot: a notification, headline, or post you couldn’t ignore.

- The voice: a person whose approval or disapproval shaped your next move.

- The weight: an unspoken assumption that made one option feel “obvious.”

At the end, review: How many of these tilts were invisible until you named them? Then share them with a friend.

In the next part in this series, we explore how we know what we know …